Neil’s V3 blog

After months of waiting and preparation, which included paperwork, training on scientific equipment and a medical examination, I had finally arrived in Hobart where in two day’s time I would be boarding the ship, the Aurora Australis bound for Mawson Station in Antarctica. For me, the journey to Hobart had been a long one, I had flown from Munich Airport to Singapore, before continuing onwards to Sydney and finally, Hobart. I arrived late Sunday evening and had pre-departure training early the next morning.

The training is compulsory who for all expeditioners who venture south and covers various aspects of the trip such health and safety, environmental issues and the risks associated with exposure in such a hostile environment. Did you know that under the worst weather conditions in Antarctica, any exposed skin can suffer from frostbite in under 2 minutes? We were also told stories about various accidents and close calls that had occurred on previous ventures down south. The one that remained with me involved an expeditioner who had ventured outside during a blizzard, he was attempting to make it to the toilet hut some 30m away, but had become disorientated under whiteout conditions and got lost. His fellow expeditioners had been unaware that he had left. They eventually realised that he was missing a few hours later, but were unable to form an immediate search party due to the severity of the blizzard outside. By the next day conditions had settled down and they were eventually able to commence a search. They found him curled up in a foetal position a few hundred meters from their shelter. At this point he was still alive, but was suffering from severe hypothermia and frostbite brought about from his exposure. Unfortunately, his conditions had detiorated to far and despite their efforts to save him, he eventually passed away.

The following day we sailed from Hobart at 11:30am (local time) under warm sunny conditions. My fellow expeditioners and I decided to take advantage of the good weather by relaxing outdoors on the upper decks, either sunbathing or watching the stunning Tasmanian coastline pass us by. I enjoyed being outside and feeling the warmth of the sun on skin knowing that in a few day’s time I would not have that luxury.

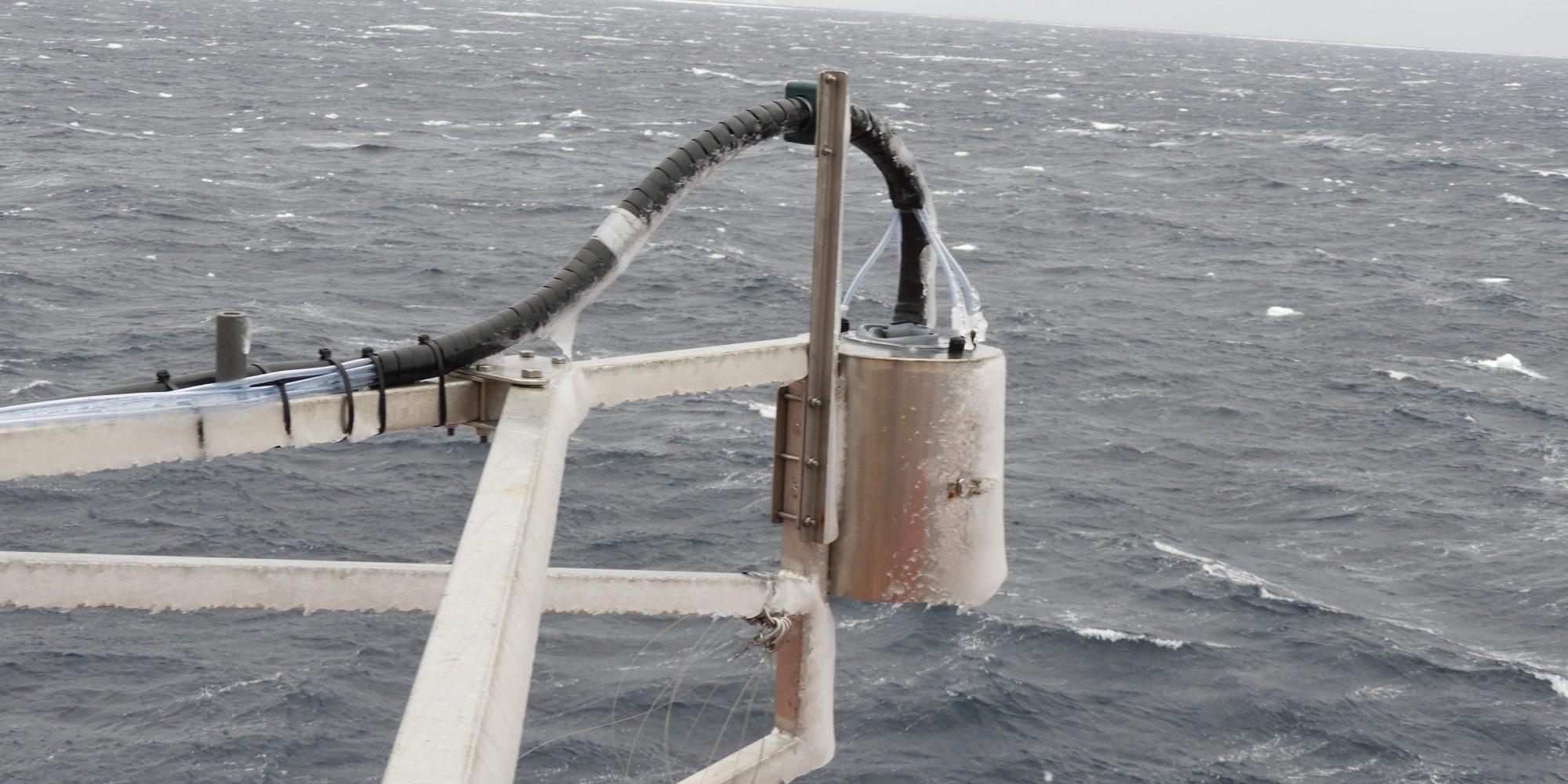

Aboard the ship I have two pieces of equipment to look after. The first is a Tekran Mercury Analyser, which we’re using to make observations of atmospheric mercury concentrations throughout the voyage. Observations of atmospheric mercury in southern-hemisphere are very limited, so the measurements are helping to provide some vital information regarding background levels over the southern-ocean and around the Antarctic continent. The second piece of equipment is MAX-DOAS, a passive spectrometer that uses both visible and UV radiation to provide a vertical profile aerosol particles and atmospheric trace gases. Looking after the equipment only takes up a couple of hours of my time each day, so I’ve offered my assistance with cleaning and launching weather balloons to the ARMs (Atmospheric Radiation Monitoring) technicians who have around 20 to 30 pieces of equipment on the top of the ship.

For the first couple of days at sea we were blessed with calm and pleasant conditions, with a light southerly breeze and waves of no more than 1-2 m. However, this wasn’t to last. Late Friday afternoon we entered a low-pressure system causing an increase in swell, wave and wind conditions. By Saturday the ship was being buffeted by large waves of 10-12m, turning any objects that hadn’t been secured into projectiles that were thrown across the cabin. Trying to sleep that night was an uncomfortable experience, to avoid ending up in a crumpled pile of limbs, pillow and doona on the floor I was forced to securely wedge myself into the corner of my bed between the mattress and wall. Somehow, I managed to survive this rough experience without feeling nauseous, although I’m not sure whether this down to pure luck or the sea-sickness tablets that I had been taking. By Sunday we had passed the low-pressure region and both wind and sea conditions had largely settled down.

TBC…

The most efficient route from Hobart to Mawson involves the ship following a circular track which takes into account the curvature of the Earth and our increasingly Southern Latitude. After 8 days at sea the ship finally crossed the line of 60 degrees south. On-board ships this is celebrated by a ceremony whereby, anyone who is crossing this line for the first time is presented with a certificate from the ship’s captain. Our progress into the cooler Antarctic waters also heralded the sighting of ever greater numbers of Antarctic bird species, including Albatross and petrels, as well as a few whale sightings around the ship.

As we slowly progressed south the Aurora Australis’ crew announced that the ship would be having a raffle and encouraged people to nominate 10 minute timeslots for the sighting of the first iceberg bigger than the ship. The raffle was eventually won by the ship’s captain, perhaps suggesting that his years of experience may have provided an unfair advantage. For me the appearance of icebergs was quite exciting. Before this trip I had never seen an iceberg in person. The closest I had come was from watching the film “Titanic” and so I decided to brave the sub-zero conditions up on deck and maximise my time taking pictures of these colossal Icey beasts.

In preparation for our arrival in Antarctica we were subject to strict quarantine measures that are imposed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). As a result, we were expected to thoroughly clean all of our personal gear, clothing and equipment to ensure that it was free from any seeds and soil that could introduce alien species into the sensitive Antarctic environment.

Up until this point our voyage had been proceeding according to plan, the ship had been making good progress and was currently 4 days ahead of schedule. However, this was not to last. The next day a spanner was thrown in the works with the news that the reverse osmosis (RO) plant at Davis Station had failed. The RO plant is responsible for providing Davis with enough fresh water to last throughout the winter. Without it operating, fresh water supplies at Davies were at risk of running out and so the ship was being diverted to provide additional fresh water.

Soon we were cruising amongst the pack-ice. For me this was quite exciting as I would finally get to see the ships ice-breaking abilities in action. Luckily for any would be photographers, the ships’ crew allowed expeditioners to stand up front at the bow of the ship where you are rewarded with a front row seat to the ship crashing its way through the ice. Ice breaking isn’t actually a result of the ship’s bow acting like a knife to cut through the ice. Instead, it’s a result of ships specially designed hull being lifted up on top of the ice by powerful engines and the ship’s own weight then splitting the ice and pushing it aside. The pack-ice also heralded the appearance of a variety of seals, including Leopard, Weddell and Crabeater seals resting lazily on the ice and raising their drowsy heads to watch as the ship cruised past. Apart from Orca (Killer Whales), Leopard Seals are one of the largest predators within the Antarctic food chain, so seeing them in the wild is a definite treat.

As the Antarctic mainland grew closer on the horizon, I finally saw my first wild Adelee penguins! I had of course seen penguins previously in the zoo, but nothing can prepare you for seeing them in the wild, running around on the pack-ice like comical little tuxedo wearing clowns. It’s so cool, this was the reason I wanted to come down Antarctica for years. Adelee penguins are completed naive though, I was watching them sit on the pack-ice in front of the ship as it bared down on them and they just stand and stare. It appears as though their brains can’t quite comprehend what they are seeing and I can just imagine them with their beaks hanging open mouthing “what!!!!!!!!” as this huge red ice-berg crashes towards them. They do eventually dive out of the way, and so no penguins were hurt during the voyage. At this point I was informed by one of my fellow expeditioners that penguins have the intelligence of a chicken, although I would like to give them a bit more credit…

We soon arrived at Davis and commenced our operations of topping up the stations supply of fresh water. At this point the Aurora Australis was anchored about 400m from the Antarctic mainland, but to the frustration of all expeditioners on-board we not have the opportunity to set foot on land and explore. After a couple of days we finally commenced on our original voyage. Two days later we arrived at Mawson, our ultimate destination. However, another spanner was about to be thrown in the works, with the news that Horseshoe harbour, where the ship was hoping to dock and commence resupply, was frozen over. It may seem ironic that an icebreaker is prevented from entering the harbour by a thin layer of ice, but the harbour is narrow and shallow and the ship can’t use its bow thrusters to properly move while amongst the ice. To enter the harbour under these conditions would risk the ship running aground. So resupply from the harbour was put on hold.

TBC….

2nd March: Mawson is situated within a natural cove known as Horseshoe harbour. As the harbour was frozen over, the decision was made for the ship to hold position about 600m from the station, just to the north of a rocky outcrop known as the West-Arm. A small party was sent ashore to help secure the ship’s mooring line and also to set up the hose that would transfer fuel from the ship to the station. I was invited to join the party to help provide some additional help, very happily I accepted the offer. We were transported ashore via a small inflatable motor-boat, known as an IRB. This was it, I had finally made it too Antarctica and could now claim to have set foot on a continent where very few people will ever have the opportunity. Undertaking this operation was a labour intensive task, made more difficult by the frigid temperatures, strong winds and heavy snowfall that were now blanketing the area. Trying to undertake any task in these conditions becomes a difficult operation as the cold temperature ensure that you are bundled up in multiple layers, while the thick gloves make already fiddly jobs far more complex. My shift lasted 4 hours. By the time it was over I was starting to feel the effects of being out in the cold and was very glad to return to the ship where I could recover over a hot drink and meal.

It was around this time that I had the first complication with the scientific equipment. While I was undertaking my morning equipment checks I noticed that a red ‘lamp’ light had flicked itself on at the front of the Tekran Mercury Analyser. The light indicates that the equipment requires a sort of calibration, via a process known as a ‘lamp adjustment procedure’. The overall aim of this procedure is to adjust the voltage supply to the lamp inside the Tekran unit. The lamp itself is essential to correctly measuring the concentrations of atmospheric mercury in the air, so fixing this issue was of paramount importance. The procedure is simple enough if you know what you’re doing and basically involves opening up the equipment, adjusting the lamp’s position and then connecting a voltmeter to calibrate the voltage to the correct level. Unfortunately for me I was unsure of exactly where to connect the voltmeter as the inside of the Tekran looks like a giant circuit board. This is where Grant Edwards of Macquarie University came to my rescue by emailing me a technical guide of how to complete the procedure, he also included his own bullet-point summary. With these in hand I returned to the equipment and after much effort, I successfully completed the calibration, mission completed.

A few days later an order came through from AAD headquarters in Hobart authorising the ship to reverse into the harbour in an attempt to dislodge and break-up the ice cover. This provided a great deal of excitement for all on board who were now gathering on the helideck and jostling for the best position to watch and film as the ship rammed the ice. The results were quite spectacular and the ship successfully cut a narrow channel into harbour. It would however take the remainder of the day and several more channels to completely break up the ice before the retreating tide removed it from the harbour.

Over the next couple of days I assisted with the resupply operations by manning the ‘bunker door’. The bunker door, is a door on the side of the ship from which a rope ladder is dropped. This provides the main route for expeditioners and crew to transfer between the ship and the IRB’s which then ferry them ashore. Working the bunker door is a fairly simple task that involves assisting passengers with the rope ladder, lowering and raising bags and keeping a record of everyone that comes and goes from the ship.

With resupply operations well underway, I was offered the opportunity to spend the day ashore exploring Mawson. This would be one of the highlights of my trip to Antarctica. The buildings at Mawson are coloured according to their purpose, red for residential and recreational quarters, green for warehouse storage, blue for power and yellow for operations. All of these buildings are interconnected by a network of ropes that help to prevent expeditioners from becoming disoriented during white-out conditions. For the duration of my time onshore I was confined to within the station limits, this is a safety precaution for anyone that has not undertaken field training as the weather in Antarctica can change very quickly. Unfortunately this meant that I would not be able to visit the penguin rookeries, but as there were a few curious penguins wandering about the station I was perfectly content.

A few days later resupply was complete and we started the long return journey back to Hobart, it would take us another 2 weeks to complete this. After all the excitement of seeing Antarctica, the return journey felt like a bit of an anti-climax, everyone was now looking forward to getting home and so the excitement which accompanied us on the trip down was now gone. As we slowly put some distance between us and the Antarctic continent, the nights began to grow longer and the sky cleared. This was fantastic because it not only provided an amazing view of the starlit sky, but also provided a tantalising view of the phenomenon which the ship is named after, the Aurora Australis, or southern lights. The Aurora results from charged subatomic particles in solar wind interacting with the Earth’s magnetic field and giving off distinctive colours. I was elated to witness this before the expedition concluded with our return to Hobart in a few days.

Categories